Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman is a guide to understanding ourselves, how we decide, and how we make mistakes. It seems basic, but it is not obvious.

This post is my summary.

In his essay, Kahneman describes rationality as coherence, internal awareness, and humans as irrational. Irrational according to this definition and without any connotation of impulsivity or emotionality.

This irrational behavior translates into decision-making in a way that is often predictable.

This summary is an extensive and somewhat dense post trying to condense the keys to Kahneman’s thinking.

In his book, Kahneman employs numerous examples and experiments that facilitate the understanding of the concepts. I will include only a few essentials.

Although the book does not address it, I believe that Daniel Kahneman’s thinking is closely related to the development of Artificial Intelligence. I will not address this topic, which I may leave for another future post.

“Intelligence is not only the ability to reason; it is also the ability to find relevant material in memory and focus attention when needed,”

Daniel Kahneman

I hope that anyone reading this summary will feel compelled to delve deeper by reading “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

What is “Thinking, Fast and Slow” about?

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” discusses our way of reasoning and making decisions. Kahneman develops his ideas through a continuous confrontation between pairs:

- Between 2 systems of thought that coexist and struggle within us: System 1 (which is fast thinking) and System 2 (which is slow and effortful thinking that tries to monitor and control System 1)

- 2 species: the econos (who live in the land of theory and represent an idealized view of people) and humans (who live in the real world and make real decisions)

- And 2 versions of the SELF: the experiencing SELF (the one who lives the experiences) and the remembering SELF (generating incorrect memories from experiences and a series of biases). It is this second SELF that ultimately makes the choices.

Based on these confrontations of pairs, the book deals with how our brain functions and, above all, how it makes mistakes. Daniel Kahneman uses psychology to delve into economics.

Kahneman also describes the origin of numerous biases that affect our personal and economic decisions, including the fact that we make decisions based on our memory and not on what we actually experienced.

Who is Daniel Kahneman?

Born in Israel and trained in France, he studied Psychology. He enlisted in the psychology department of the Israeli army. He emigrated to the United States to complete his graduate studies in psychology, collaborating on numerous projects and research with his colleague.

Amos Tversky

In 2002, Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his research and work alongside Vernon L. Smith, becoming the first non-economist to receive it.

His contribution of the prospect theory is particularly noteworthy. This theory is described in “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

In the following video from “Talks at Google,” the author himself wonderfully summarizes his essay (1 hour, English). If you prefer watching him over reading this summary, it is a good choice.

Daniel Kahneman at Talks at Google

”Thinking, Fast and Slow”: The Book

This essay consists of chapters organized into 5 blocks:

- Block 1. TWO SYSTEMS

- Block 2. HEURISTICS AND BIASES

- Block 3. OVERCONFIDENCE

- Block 4. CHOICES

- Block 5. TWO SELVES

Cover of “Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman

Next, following the structure of the book, I will describe the ideas that I find most interesting from each of these blocks.

Block 1: What Do the 2 Systems of Thought Mean?

Kahneman begins the book by introducing 2 systems of thought: System 1 and System 2.

This structure does not have a neurological translation but is a way to describe the mechanism that our mind employs in thinking and decision-making.

Below, I describe both systems.

SYSTEM 1

Image from the Book: Angry Woman

System 1 is fast and intuitive. It operates automatically and with very little effort and control. This system determines the answer to simple questions like 2+2 or intuitive ones like identifying the emotion in a facial expression (for example, in the woman in the image above). It also responds to automated actions learned through experience, such as movements while driving.

In its operation, this system tries to create coherence of thought and association of ideas.

This system has a huge influence on our thinking and our decisions. According to Kahneman, its influence is greater than we think.

SYSTEM 2

System 2 is slow. It is conscious and executes thoughts that require effort. This system determines the answer to complex questions like 27+52.

System 2 requires effort, concentration, and willpower. Therefore, while using System 2, a person cannot engage in other activities.

This system is associated with good ideas and good decisions.

Consequently, we like to think that our way of thinking is determined by System 2 (reflective and conscientious), but its level of influence is much lower than we believe.

BOTH SYSTEMS COMBINED

In using both systems, our mind tries to optimize efforts. **Since the use of System

2 is expensive, our mind tries to maximize the use of System 1.

That’s why, according to Daniel Kahneman, the dominant system is System 1. System 2 appears whenever it is necessary to solve problems that System 1 cannot handle. System 2 also comes into play by monitoring the decisions and ideas that arise from System 1.

However, System 1 seeks to simplify the real world, eliminate ambiguities, generate associations that allow us to make decisions with little effort, or even replace complex questions with simpler ones to which we can respond.

The combination of a System 1 that seeks simplification and a System 2 that tries to avoid exerting effort on seemingly coherent thoughts leads us to another key concept: WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is) or thinking that everything that exists is what we know.

“Systematic errors are the result of biases, and their recurrence can be predicted under certain circumstances.”

Daniel Kahneman

The concepts described in this first block are the foundation upon which the rest of the essay will be built.

Block 2: What are Heuristics and Thinking Biases?

Thinking Fast and Slow

In this block of “Thinking Fast and Slow,” Kahneman explains that while System 2 is capable of experiencing doubts, System 1 tends to evade them through simplifications.

To illustrate this, he discusses data and statistics, but also how our mind interprets (often incorrectly) those data and statistics.

He uses various statistical examples to explain how the size of a sample allows for the extrapolation of results to a larger group with a certain error.

Our mind, in its simplifying endeavor, tends to seek out recent memories and generalize them. If something has happened recently, we assign it a higher probability than if it has occurred more frequently but further back in time.

For example, a recent or nearby murder makes us think that the probability of murders is higher than it actually is.

In fact, if statistics contradict our recent memories, our mind tends to give more credence to these mental stereotypes than to the statistics themselves.

Once again, ease (in this case, access to information) can play tricks on us in decision-making.

“Such is the essence of intuitive heuristics: when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one, usually without noticing the substitution.”

Daniel Kahneman

Prior information (in the case of anchoring), circumstances (priming), or generalizations (halo effect) largely determine our decisions. In the last section of this post, there is a list of definitions of these and other concepts.

According to Kahneman, risk does not exist. It is a mental construct.

Managing Fears and Uncertainties

Risks do not exist outside of our minds.

Block 3. What is Overconfidence in Thinking?

In this section, Kahneman explains one of the main errors our thinking makes: overconfidence.

“Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited capacity to ignore our ignorance.”

Daniel Kahneman

People constantly try to make sense of the world by seeking its coherence. And once again, we fall into the WYSIATI effect. Our judgments are based on what we know, not on reality, which is much more complex.

We think we understand the past and, from there, we are able to predict the future.

However, many of our decisions are based on our ability to predict without considering that the information we are relying on may not be valid or complete.

Moreover, optimism leads us to errors such as the planning fallacy (overestimating our capabilities in impossible plans), while an external perspective can clearly observe those errors.

Despite all of the above, Daniel Kahneman emphasizes the importance of having confidence for human beings.

Block 4. How Do We Make Our Choices?

In this section, Daniel Kahneman discusses how we make decisions and introduces Prospect Theory; a theory whose development led him to win the Nobel Prize in Economics. This theory shifted the previously employed Utility Theory.

According to Prospect Theory, in moments of uncertainty, we deviate from rationality when making decisions and take heuristic shortcuts.

He highlights risk aversion and loss aversion as the primary criteria for decision-making. Kahneman believes that, typically, people make risky decisions when they have no less risky alternatives. In those circumstances, there is a high probability of worsening the situation with poor and risky decisions. Thus, we can turn a manageable difficulty into a complete disaster.

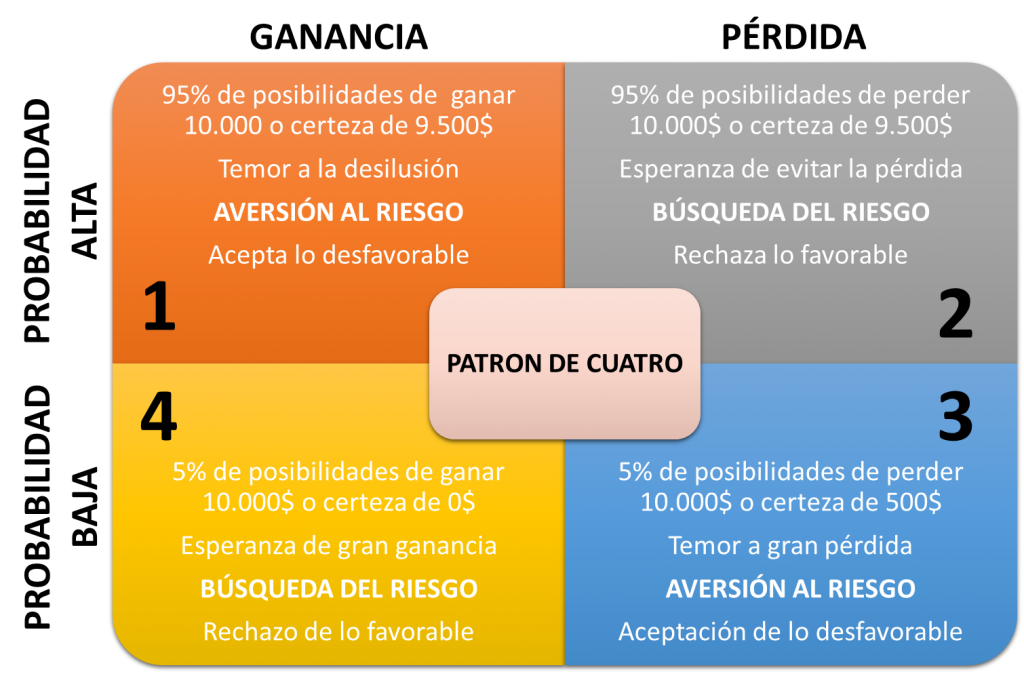

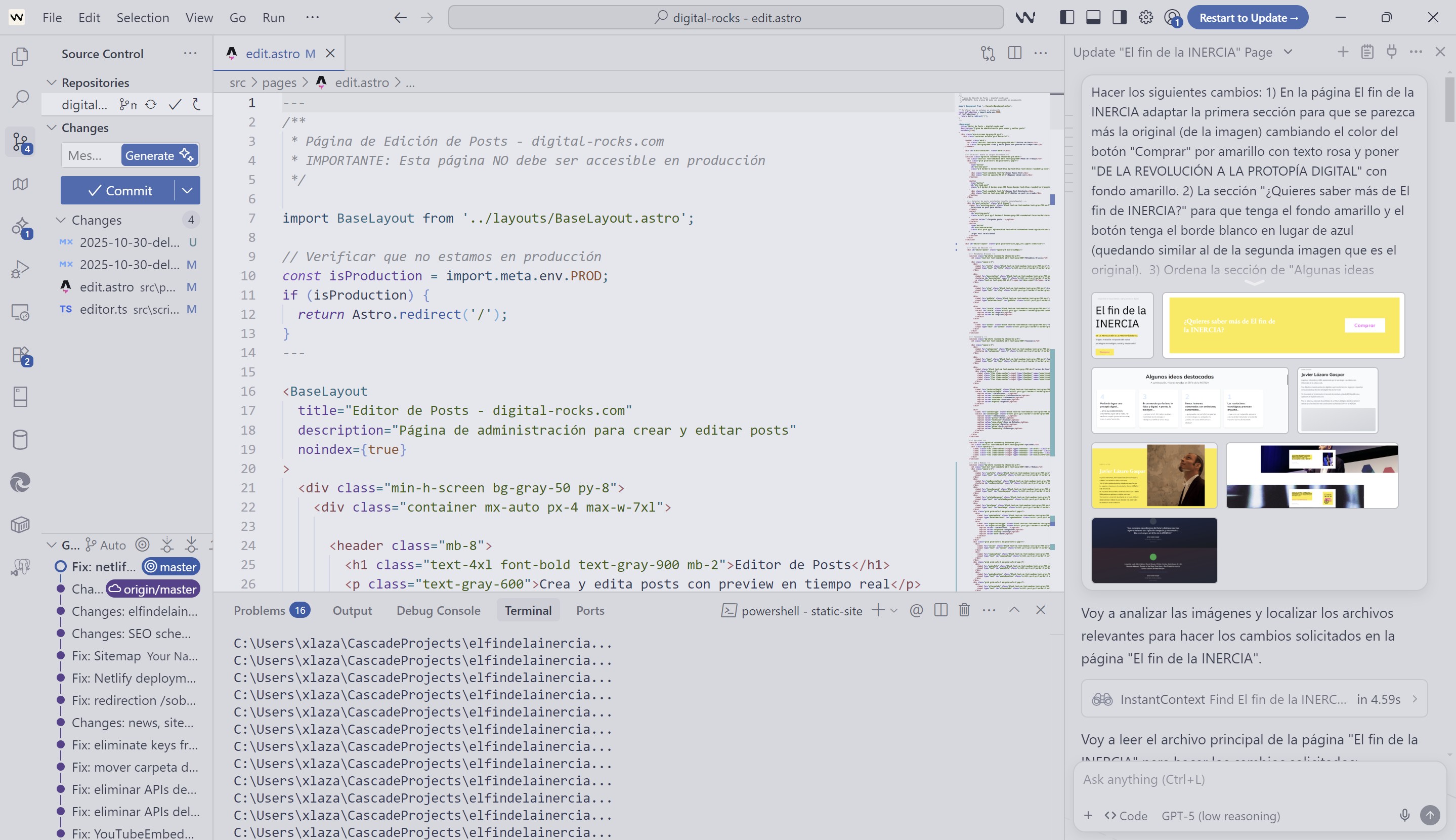

WHAT IS THE FOUR PATTERN?

The following diagram is what Kahneman refers to as the Four Pattern. The Four Pattern determines how we make decisions by considering two aspects:

- Loss or Gain: our mind behaves differently depending on whether the decision we must make is in the face of a loss (for example, we have been sued and are being claimed 10,000 euros) or a gain (we are the plaintiffs and are claiming 10,000 euros).

- High or Low Probability: the perceived probability that this loss or gain will occur.

Based on these criteria, a matrix is generated with four quadrants that determine how we make decisions: the Four Pattern.

Below, I include the example contained in the book. In each quadrant, we can see:

- An example that…

Illustrating the Decision to Be Made (Choice)

- The emotion generated by the choice: fear or hope

- Behavior that governs the decision: according to Kahneman, it can be risk aversion or (desperate) risk-seeking

- Expected attitudes: acceptance or rejection of a favorable or unfavorable situation

Below, I include an image of the Four Pattern.

“Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow”: Four Pattern

To explain this, Kahneman uses the example of a civil lawsuit. The probability is the likelihood that the person has of winning (in the left column) or losing (in the right column).

Let’s see what happens in each quadrant:

- Quadrant 1: The plaintiff has a 95% chance of winning $10,000 but accepts $9,500 to avoid the risk. The plaintiff fears disappointment and accepts the unfavorable situation. Risk Aversion.

- Quadrant 2: The defendant tries to avoid the loss, so they prefer to risk paying $10,000 (with a 95% probability) clinging to the hope of a 5% chance of not paying. The defendant decides with the hope of avoiding the loss and rejects a favorable situation. Risk-Seeking.

- Quadrant 3: The plaintiff has a very low probability of a very high benefit. Expecting a large benefit, the plaintiff rejects the favorable option. This is the example of the lottery (high benefit with negligible probability). Risk-Seeking.

- Quadrant 4: The defendant accepts paying $500 to avoid the risk of a larger loss. Faced with the possibility of a significant loss, the defendant accepts the unfavorable situation. Another clear example is insurance: we assume a certain loss to avoid the risk of a greater one in cases of low probability. Risk Aversion.

This pattern can be applied to all kinds of situations.

For example, Kahneman uses it to explain the excessive duration of wars. In them, the party that is being defeated struggles to accept the situation and prefers to cling to a tiny possibility of ultimately winning. The defeated party finds themselves in Quadrant 3 and rejects the favorable option (ending the war).

Block 5. What Do the TWO SELVES Mean?

Daniel Kahneman

This block contains an interesting reflection differentiating what we remember from what we have actually experienced.

“A story is made up of events that mean something and memorable moments, not the time that passes.”

Daniel Kahneman

To illustrate this, Kahneman introduces the concept of the two selves: the self that lives and experiences reality versus the self that remembers.

Through experiments, the author demonstrates that even the memory of what happened 15 minutes earlier is limited and can lead us to error.

This is a problem because the decisions we make are based on what we remember, which can be misleading.

It’s not what we’ve lived.

In this regard, Kahneman emphasizes that our memory gives greater weight to experiences that generate negative emotions than to those that generate positive ones. An experience can evoke both types of emotions simultaneously, but our mind will classify it into one of the two categories, avoiding the complexity of ambiguity.

Furthermore, our mind will assign less weight to experiences that occur at the beginning and greater weight to those that occur at the end of the episode being remembered.

According to the author, duration is not important in our memory. Therefore, a pleasurable experience that lasts a long time but ends with a traumatic conclusion will be remembered as traumatic by most people.

Kahneman illustrates these points (single emotion, importance of the ending, and forgetting duration) through cases of traumatic separations after years of pleasant cohabitation. In these cases, despite having spent happy years together, it is the final trauma that carries the most weight in memory.

Kahneman concludes this section by discussing Experienced Well-Being.

My conclusions from “Thinking, Fast and Slow”

In my opinion, the first section, and especially those on overconfidence and choices, are extraordinary. They alone make the book worth reading.

Kahneman is able to explain complex concepts through simple examples and experiments. He has the virtue of making it understandable for people with little knowledge of economics and none of psychology, like myself.

Moreover, understanding prospect theory (knowing that in moments of uncertainty we drift away from rationality) can help us make better decisions by identifying our thought patterns.

From an economic perspective, his undeniable value led him to win a Nobel Prize.

Perhaps, looking at it in perspective, some of the reactions described in the previous two posts (“Community and Technology Against Coronavirus” and “Ventilators with 3D Printing and IoT”) have a lot to do with what is described in Kahneman’s essay.

Additionally, perhaps in this book, Kahneman has demonstrated the keys that Eurovision commentators mention every year: short memory, better ending than beginning, duration does not matter, negative emotions versus positive ones.

Other Highlighted Concepts

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” includes a multitude of interesting concepts that I have not detailed previously to avoid extending too much.

If you are eager to know more, here are some of them in the order they appear in the book:

- WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is) is the leap to conclusions based on limited evidence.

- Priming (pre…

Disposition or Primacy: unconscious effect of information or circumstance determining our thought or judgment. For example, JA_ÓN (which can be either ham or soap). We will interpret it as JAMÓN if we are hungry; in other circumstances, the interpretation may vary.

- Cognitive Ease: measures the ease or tension (effort) that a thought generates in the mind.

- HALO Effect: generalization of virtues or defects. For example, if we like a president, we like everything they do.

- Anchoring Bias: The anchoring effect consists of estimating a value related to a quantity before estimating the quantity itself. For example, the question “Did Gandhi die at over 144 years old?” creates an anchor. If we then ask, “How old was Gandhi when he died?” the answer will be a higher number than if we had not asked the initial question.

- Outcome Bias: this refers to the bias of evaluating decisions based solely on their outcomes without considering the process or the reasons why those outcomes were good or bad.

- Illusion of Validity: this is a consequence of outcome bias. The effect makes excessively risky decisions celebrated as correct if the outcome is favorable. For example, a financial advisor with a few high-volume investments in which they were lucky may be considered more capable than another with a better average but without those standout cases.

- Assumptions and Optimism: errors in predicting the future are inevitable, but they allow us to learn. Learning that the world is unpredictable and that a lack of confidence can lead to greater accuracy. But the world needs optimists, those whom confidence blinds because they are inventors, entrepreneurs, leaders, … They are the ones capable of seeking challenges and taking risks.

- Internal/External Perspective: individuals within an organization may be blind to aspects that a new external arrival can see immediately. An example is the “planning fallacy” in which insiders tend to maximize their ability to navigate obstacles while an outsider may have a less optimistic view.

If you found this interesting, my recommendation is to grab the original and read this magnificent essay.

REFERENCES

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- Digital-rocks: Community and Technology Facing Coronavirus

- Digital-rocks: Respirators with 3DPrinting and IoT

- Gonzalo, the friend who gifted me this book.

ROLLING STONES

From a classic like Kahneman to classics like the Rolling Stones, who recorded this masterpiece during the lockdown.

I won’t say anything about their satanic majesties.

Here’s the translated content:

I remember a concert at the Calderón that I managed to attend thanks to the Patrón de Cuatro. The tickets had sold out months in advance and were being resold for prices that multiplied the original price by 10. However, just before the concert started, faced with the risk of losing the money spent on the tickets, some resellers decided to accept the unfavorable situation and sell at the purchase price to avoid the risk of loss.

To introduce the song, a Tweet from another classic:

Well, that’s it, YOU CAN’T ALWAYS GET WHAT YOU WANT!

(But if you try sometime you find

You get what you need)

Related posts

From COBOL to Agentic AI: Transforming the Software Lifecycle

Evolution of the software lifecycle applying AI and Agentic AI

Digital Transformation: Beyond Technology

In Digital Transformation, purpose and culture are more important than technology itself.

PROTOPÍA: get familiar with the term

> "Let's avoid the DYSTOPIA (...) > "Let's avoid the DYSTOPIA (...)

All opinions expressed on this blog are personal and do not represent those of any company or organization with which I collaborate.