Respiradores con 3DPrinting e IoT (Comunidad y Tecnología frente al Coronavirus parte 2)

If the previous post “Community and Technology in the Face of Coronavirus” was written from an observer’s perspective, this one comes from my comfortable second line, collaborating on emergency ventilator prototypes developed with 3D Printing and IoT components. The front line consists of those who risk their health to improve the health of others.

I don’t like to write so explicitly about initiatives in which I participate. Given the emotional intensity and objective, I will make an exception.

Over the past three weeks, I have participated in a race against coronavirus. It is a collective race aimed at ensuring that there are enough ventilators and trained professionals in hospitals to use them.

This is an ambitious goal that became more urgent and frustrating as the pandemic approached my closest circle. Everyone contributed their grain of sand.

Moreover, I believe that the lessons learned from what happened in Spain can serve other countries where the pandemic is at a less advanced stage, so the effort is not in vain.

Making Emergency Ventilators with 3D Printing and IoT, Are We Crazy?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, estimates indicated that 10-20% of diagnosed patients suffered from severe respiratory conditions. 5-10% required ICU admission with respiratory support.

For example, the UK government commissioned a consortium formed for the occasion by Airbus, McLaren, and Rolls Royce to build 30,000 invasive ventilators in 5 weeks. To do this, they were authorized to “clone” an existing commercial device.

Needs in the UK according to The Guardian

In Spain, the messages from the doctors I was in contact with were not particularly reassuring. Although it is true that, three weeks ago, the situation of an internist in Madrid and another in Seville was very different.

MECHANICAL MANUAL RESUSCITATORS

In light of the extreme need for emergency ventilators, various initiatives have emerged focused on the rapid development of invasive and non-invasive ventilation systems.

The goal is to promote local production, not of complete ventilators, but of as simple systems as possible to complement existing ones during the duration of the emergency.

These are what the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products referred to as “mechanical manual resuscitators.”

Respiradores4All

Website of respiradores4all

Such an ambitious project needs to be coordinated with a similarly ambitious platform. That platform has been Respiradores4All. Its goal is not only to have ventilators but also to ensure that there is qualified medical personnel to use them if necessary. It did not matter whether they were prototypes or commercial devices.

Respiradores4All is made up of a team of professionals who have voluntarily joined together and is supported by an incredible medical team. Without them, nothing would have been possible.

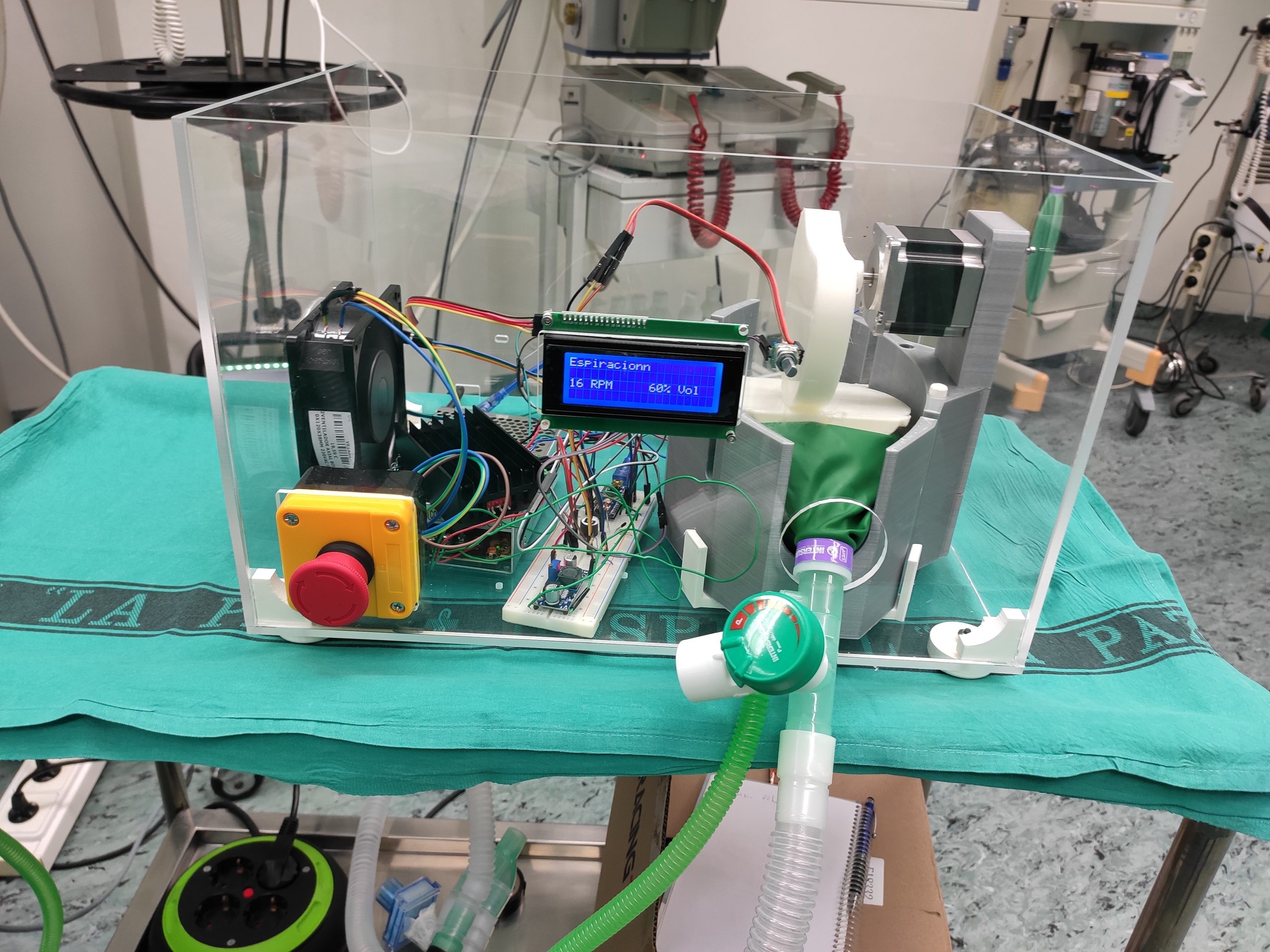

From Respiradores4All, we have worked on 3 different prototypes with three completely different technological approaches. One of them employed metal cutting, a second was 100% electronic, and the third used 3D printing.

Additionally, we are in contact with other groups in the maker and tech community trying to share experiences and identify the prototypes with the most potential, whether they were in our group or not, to accelerate them with advice, materials, logistics, etc., at a time of enormous complexity for everyone.

Respiradores4All has also launched other initiatives such as facilitating online training in mechanical ventilation for non-specialized doctors or identifying professionals who could provide support in case of extreme need.

It has connected companies and technical teams with the medical team of the group advising on equipment purchasing processes or how to adapt such equipment to Spanish needs.

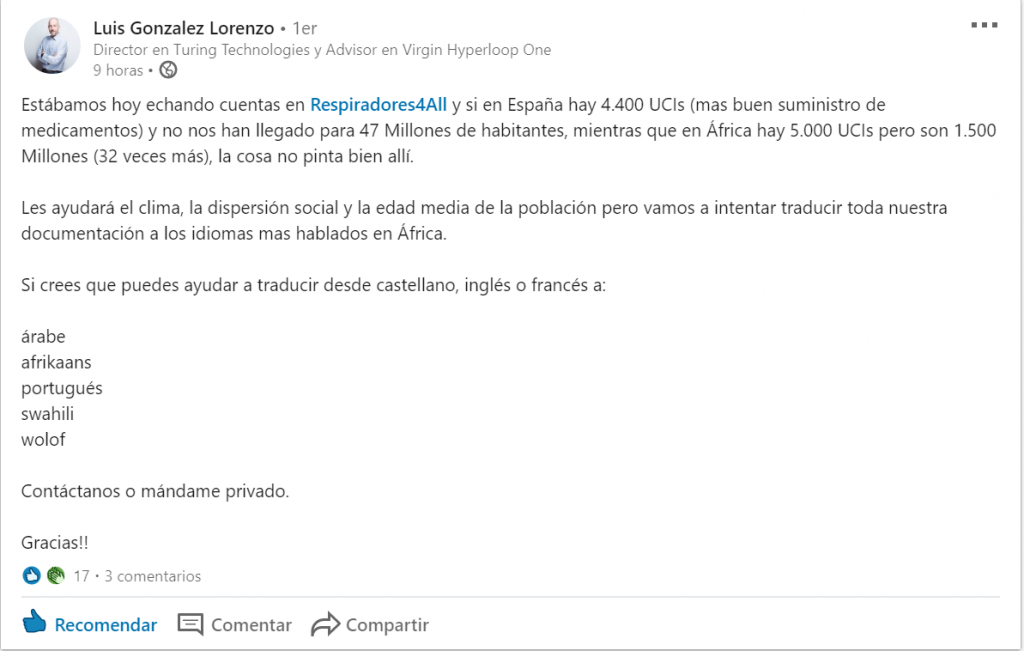

The latest initiative launched is the translation of documentation for prototypes, training, and more into various languages so that countries in Africa can benefit from the experiences of these intense weeks in Spain.

Post from respiradores4All seeking translators

We hope that many of our initiatives will not need to be used in hospitals as they aim to cover cases of extreme urgency. Success is being prepared.

Returning to the prototypes, only 1 in 10 would be authorized in time

We estimated that we had 2 or 3 weeks, and within that timeframe, at most 1 in 10 could be approved. We also needed 4 or 5 prototypes to reach hospitals to meet the needs.

We could not bet everything on one card because none of them could guarantee their functioning after a few days under the real conditions of a hospital, so having diversity would facilitate the natural selection of the best. Furthermore, having different prototypes should allow for a greater variety of components, thus reducing the risk of stockouts.

We thought that no more than 10% of the equipment would achieve certification in the necessary time (maximum 3 weeks), so it was important to support all those who attempted it. Ultimately, the number of groups working on prototypes was close to 50.

Our prototype, helpAir, was one of those nearly 50 groups working in parallel to ensure that 5 (one in ten) reached homologation. We would have liked ours to be among the chosen group, but we were satisfied thinking that without us and the other 44, there probably wouldn’t be as many at that level of maturity.

All teams had the support of the coronavirus makers community, a community of over 2,000 people willing to support such initiatives with their time, knowledge, and personal resources.

The Strength of the Maker Community

The advancements of some groups encouraged others and also reassured us. Knowing that there were other groups working in parallel relieved pressure. I don’t want to think about how a group working in isolation would have felt, knowing that lives depended solely on their success.

Twitter profile of Coronavirus Makers

News from other groups helped morale. If they have succeeded, we can too. If they are using these components, maybe we should use them as well.

But the strength of the community can also be overwhelming. We were never media-savvy. For other groups, communication gave them a special boost, but it also led to a legion of people waiting with their 3D printing equipment to get started and rush to the hospital.

This led them to isolate themselves. They went from communicating everything for a few weeks to total secrecy for the next two out of fear that what they said would disappoint or cause hundreds of people to turn on their printers prematurely.

Personally, despite how romantic it sounds, I didn’t find it feasible. I didn’t think anyone could use their 3D printer and electronic materials to replicate a device and take it to a hospital. This is a device that, if not in good condition, can kill a person or cause irreparable consequences.

If it were to go into homemade production, a testing chain would need to be established to ensure the quality and stability of all devices.

From Respiradores4All, we worked on that idea but ultimately discarded it, thinking that another path should be followed, at least in Europe.

The Dual Path of Emergency Ventilators

The path, contrary to what some in the communities claimed, was to create a functional prototype to learn, demonstrate viability, and an industrial version that could be manufactured on an assembly line.

This is, for example, the path followed by Oxygen in Barcelona alongside Seat. Oxygen currently offers 3 versions: a basic one, a pro one, and an industrial one developed with Seat.

That same approach is what we followed, developing a “maker” version and an “industrial” one.

3D Printing and IoT: Strengths in HELPAIR

In HelpAir, the name of our prototype, we set several principles:

- low cost,

- easy to replicate,

- using easily accessible components (3D printing and basic electronics),

- reliability.

This was the approach because we wanted to leverage the experience of 4 years from the Digital Hub of Ferrovial implementing complex designs in 3D printing and numerous Internet of Things projects.

Video of the disassembly and assembly of HelpAir

Additionally, the maker philosophy involves finding ways to achieve the goal with what you have at your disposal. It is not about spending as much time on design and component acquisition as in a typical project but about analyzing what you have at your disposal and seeing what you can make out of it.

This is very far from the philosophy of a large company, but in a moment of supply scarcity, it is the only way to work.

That’s why relying on our knowledge of IoT and 3D Printing was key. Working this way provided us with a solid foundation that gave us confidence that we could create something significant.

Other Designs

Other teams with different skills focused their prototypes on the use of cut metal, wood, or other materials. These different approaches enriched the whole, increasing the probability of final success and the dispersion of necessary components.

In this regard, I would like to highlight the creativity of Juan Monzón’s team with Exovite. With a very simple assembly, they made significant progress in a few days. Their prototype used 2 motors and 2 plates to press an Ambu. With great generosity, Juan and his team decided to freeze their prototype to join forces with another that, at that moment, seemed more advanced.

When possible, from Respiradores4All, we wanted to promote this type of convergence to accelerate projects and facilitate their success by combining capabilities.

Other approaches eliminated all mechanical mechanisms, replacing them with solenoid valves. These systems had the main advantage of stability since they had no mechanical components that could wear out. On the downside, some of our medical advisors were concerned about the risk of excess volume in case of problems with those valves.

A good example of this last type is RespiraAndalucía.

HELPAIR: The Development

We started from the design initially published by the Reesistencia Team and began redesigning it in the way we considered most appropriate.

Every project needs to visualize its values: design by Cristina Cruz

We maintained the use of “maker” single-thread electronics to keep costs and simplicity controlled, redesigned the mechanics and pneumatic circuit incorporating filters, pressure relief valves, and PEEP, and incorporated various pressure sensors, airflow sensors, and others to show the medical team the measured values.

During the first week and a half, we made significant progress. The feedback from medical and non-medical experts was very positive. We went to veterinary tests, and although we did not pass them, we also received positive feedback. The problems detected seemed solvable in a short time.

HELPAIR: The Specifications

But as we progressed, the level of demand also increased. Our medical team began to identify problems that had not been seen before. The UK published specifications, the first to appear publicly, with a high level of demand. We imagined that the AEMPS would soon do something similar, although it never did.

By the end of the second week, pushing air to the patient was no longer the main goal of the ventilator. The ventilator also served as a thermometer for the patient’s lung situation, displaying data on compliance and other medical terms we had never heard of.

Blowing Air into a Pig is Not Difficult

Blowing air into a pig is easy

Medical team of respiradores4All

Working in an area you are completely unfamiliar with (such as mechanical ventilation) generates uncertainty. We received optimistic messages of encouragement but also some frustrating ones. When you think you are making a significant step and realize it represents only a small portion.

For a time, the community had the feeling that the goal was to reach veterinary tests, but that was not the reality.

It was not enough to push air and read values to display on a screen. The device had to readjust its functioning according to the behavior of the lung.

Testing helpAir at IdPaz

Despite what had been achieved so far, and that we were close, the single-thread processor used did not allow us to guarantee that feedback and adjustment in real time.

The team made an attempt to integrate 2 processors that communicated with each other at a low level, but the time we did not have was increasing.

Many other teams reached the same situation. Just look at the final redesign of Reesistencia Team incorporating an embedded PC within the device.

HELPAIR: Our Weaknesses

AEMPS published its requirements, which included electromagnetic compatibility certification.

We also considered it necessary to conduct endurance tests, keeping the system running for 33,600 cycles (approximately 30 hours).

After 2 weeks without rest, with a significant challenge ahead (the correct connection of the 2 processors and adjusting the airflow based on the sensors), we estimated about 4 days for those tests.

The time limit was running out, and as often happens in such cases, weaknesses became more evident.

The first, the supply chain. Both in healthcare and electronic components, it was impossible to obtain them in the right time. If it was initially difficult, at that moment we had a motor held up in customs in Spain and a flow meter in Italy.

If it was hard to get one unit, getting 2 or more units of each component was impossible. The team tried to resolve these shortages with homemade solutions that made tasks that could be done in hours take days.

The gap with the prototypes that had started a week earlier, had been faster, or used other components began to grow. It was not important if they arrived, but it was a problem if they faced the same supply difficulties.

The second, we were working remotely, from home, with a single instance of the prototype at one person’s home, and no matter how much they worked, it was impossible to integrate the work of others while advancing in their part. Although other teams could support us, we did not have the capacity to distribute the work further, and creating a copy was a task that took 1 or 2 days.

Let alone starting final tests with that single instance. It meant that during the testing week, we had to stop all developments.

Finally, the fatigue from working 16 hours a day made it essential to slow down.

HELPAIR: The Industrial Alternative

From the beginning, we had in mind an industrial version in addition to the maker one.

Given the situation, the most effective alternative was to stop the developments of the maker version and go directly to the industrial one. Despite having advanced designs, we considered an effort of another 2 weeks plus one for testing.

We knew that other teams that had started down that path were also struggling, and again, the supply chain for certain components generated additional uncertainty.

At that moment, a group of 5 prototypes was about to be authorized by the AEMPS to proceed to clinical trials with humans. We were beginning to feel that the objective as a group was being fulfilled.

HELPAIR: The Result

HelpAir in operation

Despite feeling close, given the difficulties we faced, we decided to discontinue development. Rest and dedicate 2 days to prepare all the documentation for it to be published openly.

After 3 weeks, we have returned it to the community under GPL/GNU v3 license so that anyone who wants to use this information for non-profit purposes can do so.

We hope that this documentation can be used as a basis for other developments (of invasive or non-invasive campaign ventilators) or as a reference by national or international teams wishing to work on their own developments.

After the intense effort, we have returned to the community what belongs to it: the designs we have made of an incomplete prototype of an invasive campaign ventilator.

You can access all the documentation here:

https://gitlab.com/helpair/helpair

Currently, there are 4 prototypes that have already achieved authorization to begin clinical studies, and one that seems to stand out for its capacity to be industrialized: Oxygen with Seat.

According to news published in El Periódico, at the time of closing this post, Seat has already produced more than 500 units and has halted production. It seems that the needs in hospitals are beginning to be met due to the decrease in emergency admissions. We hope that the trend continues and these emergency devices will no longer be necessary.

And now, what?

Current news about the importation of equipment, increased national manufacturing with Hersill (we hope they are not limited by the component supply issues we observed), the advances of various prototypes, and the possible flattening of the curve lead us to believe that ventilators in Spain will soon cease to be a problem.

That said, both from respiradores4All and from HelpAir, we offer to collaborate with our experience in the work that other national or international teams are undertaking on projects with the same objective.

As I mentioned in the introduction, I believe that the lessons learned from what happened in Spain can serve other countries where the pandemic is at a less advanced stage.

We continue to work in that direction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

HelpAir has represented a colossal effort from Adrián de la Iglesia Valls, Jorge Vallejo Fuentes supported by Alejandro Pérez Ayo, Francisco Iglesias Sánchez, Ignacio Losas Dávila, and Cristina Cruz Aparicio. In the final stage, David López and Mariano de Diego also joined with their industrial design knowledge and experience.

I would also like to thank Sngular, CI3, and, especially, Ferrovial for their support in material and personal resources to carry out HelpAir.

Respiradores4All would not have been possible without Jose Luis Vallejo, Luis González, Paco González-Blanch, Juan Monzón, Ricardo Forcano, Eloi Cortés, Alejandro Fernández, José María Marzal, Manuel de la Matta, Rocío Díez Munar, and Carlos Yébenes. The last 5, the medical team that supported us. Without them, nothing would have made sense.

And to all the known and unknown, companies and individuals, who during these weeks have given us their time and resources altruistically to carry out both projects.

#WeStopThisVirusTogether

REFERENCES

- Government chooses design of ventilators that UK urgently needs

- Community and Technology in the Face of Coronavirus

- helpAir

- Oxygen

- The ‘Andalucía Respira’ ventilator, pending approval by the Medicines Agency

- BBVA: What is the best use of non-invasive ventilators against coronavirus?

- Respiradores4All

- Seat will pause the production of ventilators after verifying a decongestion of ICUs

FRANCO BATTIATO

This is not a normal moment nor a usual post, so I will not include rock music either.

A friend reminded me the other day of this song. I don’t know why, but I think it fits very well with the current situation.

Let’s enjoy “Permanent Center of Gravity.”

Related posts

From COBOL to Agentic AI: Transforming the Software Lifecycle

Evolution of the software lifecycle applying AI and Agentic AI

Digital Transformation: Beyond Technology

In Digital Transformation, purpose and culture are more important than technology itself.

BIG TECH CAPITALISM by Evgeny Morozov

'Big Tech Capitalism' shares many of the issues I describe in 'The End of Inertia' but does not approach them in the same way, as its author starts from an e...

All opinions expressed on this blog are personal and do not represent those of any company or organization with which I collaborate.